Different Types of Panic Attacks: An Overview

The Essence of Generalized Panic Attacks

Generalized panic attacks, often misunderstood as abstract episodes, represent a spectrum of intense fear responses with applications across psychological and physiological studies. These attacks provide a revealing framework for analyzing how the body and mind interact under extreme stress, uncovering patterns that standard anxiety models might overlook. Clinicians find this perspective particularly valuable when traditional diagnostic tools fall short.

By examining panic attacks through this lens, we gain structured methods to identify connections between seemingly unrelated symptoms—like rapid heartbeat and derealization. This approach fosters a more integrated understanding of panic's underlying mechanisms.

Distinguishing Features of Generalized Panic

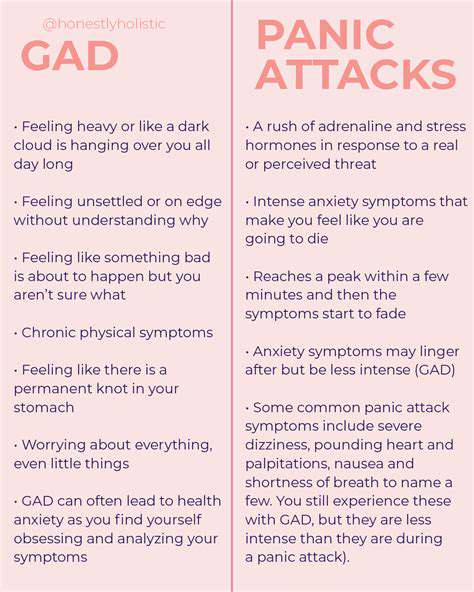

Three core features define generalized panic episodes. First, they transcend specific triggers, often arising without obvious provocation. This unpredictability makes them particularly distressing, as sufferers can't anticipate or avoid onset. Second, their physical manifestations (tachycardia, hyperventilation) frequently mimic life-threatening conditions, creating a feedback loop of escalating fear.

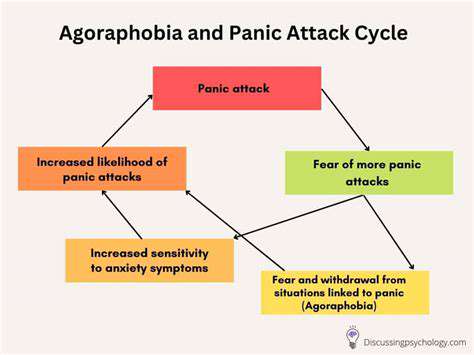

The cyclical nature of these attacks demands attention. Many patients experience fear of fear between episodes, where anxiety about future attacks actually precipitates them. This self-perpetuating pattern requires targeted therapeutic interventions to break the cycle.

Cross-Disciplinary Implications

Generalized panic's complexity makes it relevant across multiple fields. Neurologists study its amygdala activation patterns, while cardiologists research its cardiovascular effects. Psychologists, meanwhile, examine how cognitive distortions fuel these episodes. This multidisciplinary approach yields more comprehensive treatment strategies than any single specialty could provide.

For example, emergency room protocols now incorporate panic attack screening to distinguish them from cardiac events—reducing unnecessary medical interventions while ensuring appropriate care.

Treatment Challenges

Despite therapeutic advances, significant hurdles remain. The very nature of generalized panic—its lack of predictable triggers—complicates exposure therapy approaches. Many patients struggle with medication side effects that paradoxically mimic panic symptoms (e.g., beta-blockers causing fatigue).

Perhaps the greatest challenge lies in patient education. Helping sufferers understand that panic attacks, while terrifying, aren't physically dangerous requires careful communication to avoid minimizing their distress.

Emerging Research Directions

Current studies focus on several promising areas. Neurofeedback training shows potential for helping patients regulate physiological responses. Genetic research is identifying biomarkers that might predict treatment responsiveness. Most crucially, researchers are developing hybrid therapies that combine pharmacological interventions with VR-assisted exposure techniques.

Another frontier involves studying how lifestyle factors—sleep quality, gut microbiome health—might influence panic susceptibility. This holistic approach could revolutionize preventative care.

Situational Panic Attacks: Triggers and Responses

Defining Situational Panic

Situational panic attacks differ fundamentally from generalized episodes by their predictable triggers. The hallmark of these attacks is their consistent association with specific circumstances—whether crowded spaces, medical procedures, or performance situations. This predictability paradoxically offers therapeutic advantages, as triggers can be systematically addressed.

Interestingly, the triggers themselves often symbolize deeper fears—flying might represent loss of control, while public speaking could tap into rejection anxiety. Effective treatment requires unpacking these symbolic layers.

Common Trigger Patterns

While triggers vary individually, several categories emerge consistently:

- Confinement situations (elevators, MRI machines)

- Social evaluation scenarios (job interviews, first dates)

- Medical environments (dentist chairs, injection clinics)

The intensity often relates not to the situation's objective danger, but to perceived escape difficulty. A crowded theater becomes threatening not due to the crowd itself, but because leaving mid-performance feels socially unacceptable.

The Anticipation Cycle

Pre-event anxiety frequently outweighs the actual encounter's distress. Many sufferers report pre-panic symptoms days before anticipated triggers—insomnia, digestive issues, and obsessive rumination. This anticipatory phase often proves more debilitating than the panic attack itself, as it represents sustained suffering.

Cognitive restructuring techniques specifically target this phase, helping patients distinguish between probable outcomes and catastrophic predictions.

Life Impact Considerations

The ripple effects of situational panic extend far beyond the attacks themselves. Career trajectories shift as sufferers avoid promotions requiring public speaking. Social circles shrink when gatherings trigger anxiety. Perhaps most insidiously, sufferers often develop compensatory behaviors—always sitting near exits, carrying safety medications—that reinforce their fear.

Effective treatment must address these behavioral adaptations alongside the panic symptoms themselves.

Innovative Treatment Approaches

Beyond traditional CBT, several novel interventions show promise:

- Interoceptive exposure (deliberately inducing harmless physical sensations)

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) techniques

- Biofeedback-assisted relaxation training

Contextual exposure therapy has proven particularly effective—gradually introducing triggers while teaching coping skills, rather than mere avoidance.

The Importance of Professional Guidance

While self-help strategies exist, professional assessment remains crucial. Many physical conditions (thyroid disorders, arrhythmias) mimic panic symptoms. A thorough evaluation ensures proper diagnosis and prevents misattribution of potentially serious medical issues.

Moreover, therapists can identify subtle trigger patterns patients might overlook, and tailor interventions accordingly.

Panic Attacks with Agoraphobia: Fear of Fear

The Agoraphobic Paradox

Agoraphobia transforms panic disorder into a spatial phenomenon, where geography becomes a minefield of potential terror. What begins as fear of panic attacks evolves into fear of places where attacks might occur—creating ever-shrinking safety zones. This progression often follows a predictable sequence: first avoiding the site of the initial attack, then similar locations, eventually restricting oneself to safe spaces.

The cruel irony lies in how avoidance behaviors, initially protective, ultimately reinforce the phobia. Each avoided situation becomes proof of its inherent danger in the sufferer's mind.

Symptom Complexities

Agoraphobia manifests along a spectrum from mild (preferring familiar routes) to severe (housebound). Common manifestations include:

- Requiring safe person accompaniment

- Developing elaborate avoidance rituals

- Experiencing anticipatory anxiety hours before leaving home

The condition often involves safety behaviors that maintain the illusion of control—like carrying anti-anxiety medication everywhere, even if never used.

The Neurobiology of Avoidance

Recent fMRI studies reveal how agoraphobia alters brain function. The hippocampus—responsible for contextual memory—overgeneralizes threat associations. Meanwhile, the prefrontal cortex (which normally modulates fear responses) shows decreased activation. This neural profile explains why logical reassurances often fail—the fear response operates at a primal level.

Understanding this biology helps explain why exposure therapy must be gradual—the brain needs time to rewire these maladaptive pathways.

Treatment Innovations

Modern approaches combine several evidence-based strategies:

- Graded exposure hierarchies (systematic desensitization)

- Cognitive restructuring of catastrophic thoughts

- Mindfulness techniques to tolerate discomfort

Technology-assisted therapies show particular promise, from VR exposure programs to GPS-based anxiety tracking apps that help patients visualize progress.

The Recovery Process

Recovery typically follows a non-linear path, with breakthroughs and setbacks. Key milestones include:

- Tolerating anxiety without escape behaviors

- Expanding safe zone boundaries

- Developing self-efficacy in managing symptoms

Relapse prevention strategies become crucial during stress periods, as agoraphobia often reemerges during life transitions or trauma.

Understanding Panic Attacks in Specific Populations

Adolescent Panic: Developmental Factors

Adolescent panic attacks often reflect developmental tasks—establishing identity, navigating peer acceptance, and developing autonomy. The still-maturing prefrontal cortex struggles to regulate the amygdala's fear responses, making teens particularly vulnerable to panic spirals. Social media amplifies this by creating constant performance pressure and comparison opportunities.

Effective treatment must account for developmental stage—for instance, framing exposure exercises around age-appropriate goals like attending school dances rather than generic social situations.

Geriatric Panic: Overlooked Realities

Late-life panic often gets misattributed to physical decline. Key considerations include:

- Medication interactions mimicking anxiety symptoms

- Loss-related triggers (widowhood, retirement)

- Sensory impairment exacerbating disorientation

Cardiac and respiratory conditions must be definitively ruled out, as panic symptoms in elders frequently warrant medical workups before psychological intervention.

Disability-Related Panic Considerations

For individuals with disabilities, panic often intersects with:

- Accessibility barriers increasing situational anxiety

- Communication challenges complicating symptom reporting

- Pain conditions lowering panic thresholds

Treatment adaptations might include modified relaxation techniques for limited mobility, or incorporating assistive technology into exposure exercises.

Cultural Contexts in Panic Expression

Cultural factors influence how panic manifests and is perceived:

- Somatization patterns vary by culture (e.g., more cardiac symptoms in Western cultures)

- Help-seeking behaviors differ across ethnic groups

- Stigma levels impact treatment adherence

Clinicians must recognize how cultural narratives shape panic experiences—whether viewed as spiritual crises, medical conditions, or moral failings.

Gender Differences in Panic Presentation

Research consistently shows women experience panic disorders at twice the male rate, possibly due to:

- Hormonal influences on stress response

- Socialization differences in emotional expression

- Greater likelihood of seeking treatment

Men more often report anger attacks rather than classic panic, potentially leading to underdiagnosis in male populations.